Warszawa 2025-02-14

The Warsaw-Petersburg Iron Road.

The Warsaw-Petersburg Iron Road (Варшавская – Петербурго железная дорога). Remember that St. Petersburg was the capital of the Muscovite state at the time. The Warsaw-Petersburg Iron Road was built with a track gauge of 1524 mm. It had a total length of 1,333 km. The course of the line: St. Petersburg – Gatchina – Luga – Pskov – Dvinsk – Vilnius – Grodno – Białystok – Łapy – Warsaw. The journey between the final stations took 38 hours at that time, while on the Warsaw-Vilnius route the train traveled 14.5 hours.

It is assumed that the world’s first railway line was opened in the UK on September 27, 1825. Although horse traction had been in operation earlier. In the period 1844-1848, the Warsaw-Vienna Railway was launched. In the period 1860-1862, the Warsaw-Petersburg Railway was launched, which was the second in Poland during the partitions. It should be noted that projects to build railways were hindered by the Muscovites, just as currently (2025), the Central Communication Port (CPK) projects are being hindered by the Volksdeutsche, communists and freemasons. It should be remembered that the Moscow state in the 19th century was backward. It was an agricultural country, but with a low culture of cultivation and breeding. Illiteracy was about 80%. The Crimean War (1853-1856) exposed technical and military backwardness. In addition, Tsar Nicholas I was reluctant to use railways. Against this background, the Kingdom of Poland was at a much higher level.

The location of Warsaw on important trade routes; east-west and north-south, had to lead to the connection of two railway systems; the European and the broad-gauge Moscow. As a result, initially two, and soon four, independent railway stations were built in Warsaw. Warsaw Wiedeńska (Marszałkowska Street and Alej Jerozolimskie) on the western bank of the Vistula and on the eastern bank of the Vistula; the Petersburski station (later Wileński), the Terespolski station (currently Warsaw Wschodnia) and the Nadwiślański station in Pelcowizna. The transport connection between these stations was established in 1864, when the Kierbedzia bridge over the Vistula, with a horse tram line, was put into use. In 1876, the so-called Circular Railway was launched, with a railway bridge at the Citadel, which connected the railways on both sides of the Vistula.

All these investments were inspired by Polish industrialists and bankers, who always looked to the future with a perspective. However, the Muscovite state was clearly opposed to these initiatives, seeing them as a threat to the empire. The Muscovite government, one after another, threw into the trash applications for concessions to build specific railway lines. After the Warsaw-Vienna Railway was built, the tsarist government blocked the construction of further railway lines for several years. However, seeing the benefits in the transport of goods and passengers by rail, it agreed to the construction of the Warsaw-Petersburg Railway.

This was a time when the Germans had already built hundreds of kilometers of railway lines. For example: The Bydgoszcz-Gdańsk section, 156 km long, was put into service in 1852. In 1853, the Malbork-Elbląg-Königsberg section, 134 km long, was put into service. So the Muscovites were far behind. It was already impossible not to see the benefits of the railway. In the Muscovite state, after many efforts and military arguments, in 1842 a short section of the railway was built from St. Petersburg towards Moscow. It was a demonstration of the possibilities of the railway, not a utility railway.

Finally, the tsar had to give in and issued a concession for the construction of the Warsaw – St. Petersburg Railway, which was led through Belarusian and Lithuanian territories. The Muscovites established their own rail gauge of 1524 mm. This was dictated by military considerations. A different track gauge prevented its use by Prussia and Austria. There were also other fortifications. The line could not run through cities, so that the railway would not be used to capture cities. The line was subordinated to military and strategic goals. It was allowed to co-finance the investment from the tsar’s treasury. The laying of the line was ordered to Major General Gerstfeld.

The concession for the construction of the Warsaw – St. Petersburg Railway was issued by Tsar Nicholas I on February 15, 1851. The Tsar had the final say on the route of the route. However, the following years were spent in discussions about the route of the route. In 1853, the Crimean War broke out, which also halted the construction of the line. On 26 January 1857, it was decided that the investment was of primary importance and nothing happened further. Ultimately, the concession was granted to the Main Society of Russian Railways. The Main Society for the Construction of Russian Railways was also based on French capital, represented by Izaak and Emil Preire; representatives of the Parisian Credit Mobillier. Their agent in Poland was Leopold Kronenberg, a Warsaw banker related to Jan Gottlieb Bloch, who for some time tried to obtain a concession to complete the line. The main architect of the construction on the line was Ksawery Aleksander Skurzyński (Skarżyński) (1819–1875). Many Polish engineers, mainly graduates of St. Petersburg technical universities, also worked on the construction and later operation of the line.

In 1851, under the supervision of Stanisław Kierbedź, the line was marked out in the field and design work was carried out, and in May 1852, construction work began. During the design, the maximum gradients of 6‰ were assumed, and the minimum curve radii of 1,065 m. Unlike the St. Petersburg – Moscow line, the line was initially supposed to be a single-track line. Only the initial section St. Petersburg – Gatchina, 45 km long, was built as a double-track. However, the construction of a second track was already considered at that time.

At that time, a regulation was issued that allowed land to be taken from owners for the construction of a railway. It prohibited landowners from objecting to the acquisition of land for the construction of a railway. Sometimes even without compensation. Corruption was rampant. Commissioners-agents were appointed to take over land. Acts of land acquisition were written on ordinary heraldic paper, without paying mandatory fees. Even land that was pledged to credit institutions was taken over. In Lithuania, the opportunity was taken and an agrarian reform was carried out and serfdom was abolished. You can imagine the confusion. According to the Tsar’s regulation, the fee for land enfranchised for the construction of a railway was to be paid to the person who had it at his disposal. But this was often determined by the commissioner-agent. Therefore, land for the railway was transferred to emancipated peasants and in theory they should have received money for the expropriation. However, the peasant had to pay a temporary fee to the landowner. Of course, the peasant did not have these funds. The Main Company of Russian Railways did not indicate any conflicts in the expropriation in its reports, because all matters were settled by request, threat and bribe. The applicable fee schedules were interpreted at the discretion of the commissioner-agent. According to the reports, compensation for expropriated lands was relatively high, but most of the money went into the private pockets of the commissioners-agents. The wronged peasants were unable to defend their interests in the tsarist institutions. The deceived peasants often hired themselves to work on the construction of the railway.

Construction work resumed in 1858, but very little was done. There were major problems with the delivery of materials for construction and the appropriate number of workers. The workers were assigned to units called “Artele” (артель). There was no specified number of workers in a given unit. The head of the unit was the organizer of the works, who had under him the starostas of the artals, and they already managed the workers. In the event of a worker’s illness, 20 silver kopecks were deducted from his salary daily (15 for food and 5 for medicine). In the event of a worker’s death, his debt was paid by the entire artel. Collective responsibility was in force. Workers lived in barracks without sanitary facilities, which is why smallpox, cholera, plague and other diseases were spreading and the mortality rate was high.

It is not difficult to guess that there were strikes. The first recorded workers’ strike took place on July 4-28, 1861, when 49 stonemasons refused to start work. Several of them went to Vilnius on a delegation. The workers’ complaint was not recognized and on July 28, 1861, the organizers of the strike were flogged and forced to return to work, on unchanged conditions.

In total, 40,000 workers worked on the construction of the line in 1859–1860. After the Crimean War, the army was also sent to build the line. For this purpose, in 1858, the first military work brigade was formed.

During the work, mainly human muscle power was used. Temporary narrow tracks were built, along which wagons with materials were pushed. This is how embankments, excavations and wooden crossings over watercourses were created. In 1860, when the first sections of the tracks were already laid, locomotives and wagons appeared, which delivered the necessary material.

The bridge over the Vilia River, 30 fathoms long, was built in France. The bridge structures were assembled on the river bank and pushed onto temporary wooden supports. Then permanent supports were built. The length of the bridge over the Vilyanka River was 34 fathoms. The construction of the bridge was completed in October 1861. The bridge over the Waka River was assembled in Kaunas, divided into several parts, and brought to the site by rail. It was the same bridge as the bridge over the Vilnia River. Its length is 37.5 fathoms. Its construction was completed on December 18, 1861. Other bridges were built in a similar way. A fathom is a measure of length, which is approximately 2.1 m.

On September 24, 1861, a steam locomotive, a loose locomotive, drove along the entire railway line. But the route was not yet completed, because not all the embankments had been reinforced yet. There were also no railway traffic control devices. This work was completed in December 1862.

On September 4, 1860, the first train arrived at the Vilnius railway station. Vilnius was one of the intermediate stations on the route of the Warsaw-Petersburg Railway that was being built at the time. The station building itself was built in 1862 and survived until World War II, when it was destroyed. It was rebuilt in 1950 and renovated in 2000. In 1860, construction of a locomotive shed with 12 stations began in Vilnius. A pipeline was built to irrigate the steam locomotives, pumping water from the river. In 1875, a magnificent round locomotive shed was built in Dvinsk according to the design of P. Salmonowicz.

In 1875, the introduction of shape semaphores began. At that time, the tracks were modernized. A heavier type of surface was used and some bridge structures were rebuilt and replaced.

The most important structure on the Daugavpils – Vilnius – Grodno section was the tunnel in Ponary, the construction of which began on January 15, 1859. The tunnel was built by French and Germanic miners. On November 26, 1859, a tunnel was dug for a single-track line. It was the first tunnel in the entire Muscovite state. However, the tunnel had to be widened to accommodate a second track. The work was completed on September 15, 1861. The ceremonial opening took place on October 3, 1861, in the presence of Tsar Alexander II.

Regular traffic on the Petersburg – Vilnius – Warsaw route was launched on December 27, 1862. In total, the Warsaw – Petersburg Railway had a length of 1,611 km (1,510 versts), of which about 150 km was in the Kingdom of Poland. 63 passenger and freight stations and three stops were built on the line. Due to the prestigious importance of the new railway, churches and representative stations in the style of St. Petersburg classicism were built at the largest stations.

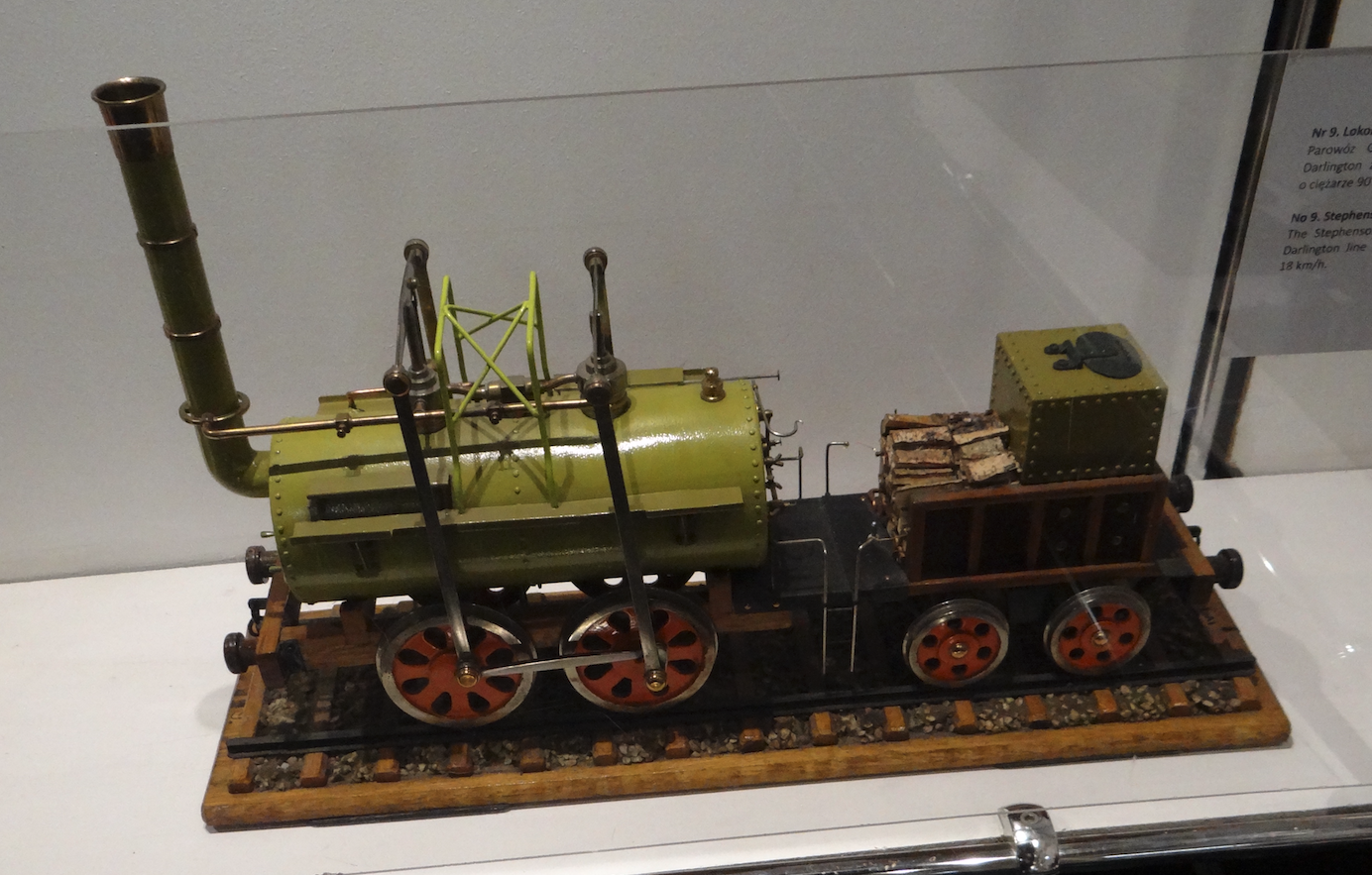

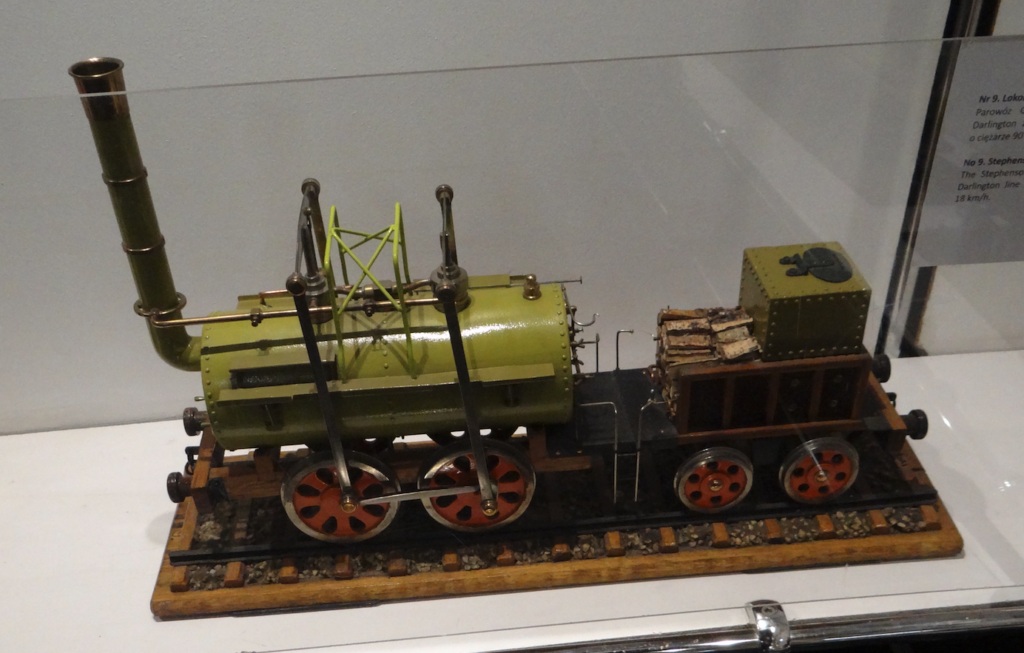

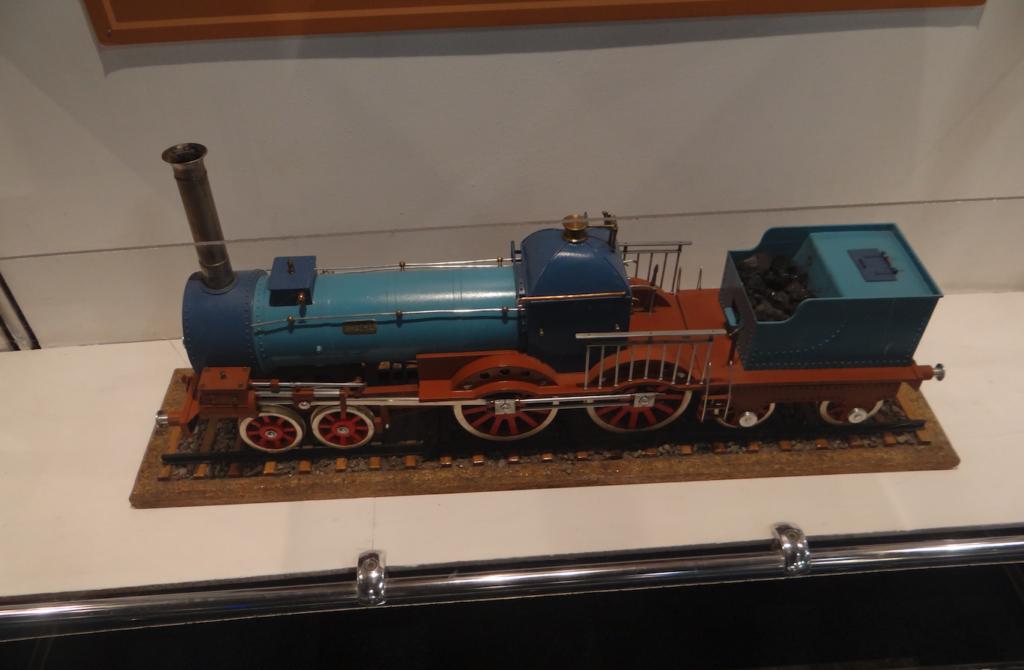

Initially, steam locomotives for the railway were purchased from Western European factories. It was not until around 1890, at the end of the 19th century, that locomotives of their own production were introduced. Although the first Moscow-made steam locomotive was built in 1845, at the Aleksandrovsky Plant in St. Petersburg. This locomotive was modeled on British designs and at that time it was a toy for shows. In 1863, the rolling stock of the Warsaw-St. Petersburg Railway consisted of: 373 steam locomotives, 819 passenger cars and 7,545 freight cars. In 1865, 1,596,117 passengers traveled on the line. The journey between the final stations took 38 hours at that time, and from Warsaw to Vilnius it took 14.5 hours.

Until 1860, rails were imported from England and Belgium, and after their production was launched at the Ural metallurgical plants of Demidov and Yakovlev, the Muscovite state had its own rails.

In 1895, the Warsaw-Petersburg Railway was bought and nationalized by the tsarist government. On January 1, 1894, a decree was issued on the nationalization of the railways, which also included the Warsaw-Petersburg Railway.

A major undertaking related to increasing the line’s capacity was the laying of a second track, 1,205 km (1,130 versts). On the entire line from St. Petersburg to Warsaw, the construction of the second track was finally completed in 1897.

In 1915, due to the Great World War, Moscow troops carried out a complete evacuation of the line’s rolling stock and railway equipment, as well as railway and customs personnel. The planned destruction of many station buildings, engineering and technical facilities and structures was also carried out. In this way, the Petersburg Railway Station in Warsaw was destroyed. During the advance of the Prussian army to the north-east, the tracks were rebuilt to the European gauge of 1435 mm.

After 1918, the line found itself in several countries. Due to the isolation of the Moscow state and the poor relations between Poland and Lithuania, the line lost its character as a main railway line.

The Polish part of the Warsaw – St. Petersburg Railway.

In Poland, the first information about the construction of the Warsaw – St. Petersburg Railway was published in the newspaper “Kurier Warszawski” on December 3, 1851. The article contained the words of Paskiewicz, the Russian governor, about the commencement of the construction of the line. It was also reported that the length of the Praga – Białystok section would be 170 versts. The line was marked in a north-eastern direction. According to the plan, the line bypassed the cities of Jadów, Brok and Wysokie Mazowieckie. The bridges were to be built on the rivers: Bug, Liwiec and Długa.

In 1852, the Polish engineer Stanisław Kierbedź was appointed to the position of deputy director of railway construction. Other Poles also worked on the construction of the line, such as the civil engineer, hydrologist and inventor Stanisław Janicki. From 1853, the construction was attended by the Warsaw financier Jan Gotlieb Bloch, also the later author of a valuable 5-volume work on the impact of railways on the economy.

The Polish section of the line had a positive impact on the economic development of towns on the route, such as Białystok and Łapy. Railway workshops were built in Łapy, which were later transformed into a large Rolling Stock Repair Plant. There is no doubt that technology revives the economy and, as a result, increases the wealth of society. The construction of railways and plants servicing rolling stock and train traffic in Tłuszcz and Małkinia caused these small villages to enter the path of accelerated economic and urban development, reducing the distance separating them from nearby towns. As a result of the development of the towns, the number of inhabitants increased rapidly, the educational system was developed, parishes and cultural and social organizations were established.

In 1859, the “Tygodnik Ilustrowany” reported that 15,000 workers were employed in earthworks alone, supervised by Mikołaj Skwarcow. In order to gain the sympathy of the landowners whose lands the railway ran through, a regulation was introduced that alcohol could only be purchased from a distillery belonging to the owner of the land on which a given group of workers worked. This was important because the sale of alcohol was one of the main sources of income for the landowners.

A major problem was the acquisition of land on which the line was to run. There were complaints from owners, indicating unfair and unequal treatment of compensation. A report by Stanisław Wysocki, who supervised the purchase of land for the construction of the Warsaw-Vienna Railway, was of great help. According to this report, most agreements were concluded voluntarily, and people who inflated land prices resigned after the district chief intervened in the matter. The biggest problem was with peasants, who often lost all their land. Those who did not lose land, due to the railway not building drainage ditches, had their fields flooded. The most honest case was always made by peasants who did not want to harm themselves or others.

Skilled workers received from 30 to 45 rubles for work throughout the season, i.e. from early spring to late autumn. Workers employed in earthworks earned from 15 to 25 rubles. Absences were deducted from wages. The work was hard, because it was mainly performed by human muscle power. There were numerous conflicts between workers and between workers and management. On May 26, 1859, the construction management asked Warsaw to assign gendarmes or Cossacks. As a result, 4 gendarmes appeared to maintain order. The workers were deprived of their documents, which were kept in the construction offices so that the workers would not escape from the construction site.

In 1861, on the Polish section of the line, in the area of Łapy station, there was also a workers’ strike. Due to delays in the schedule, Jan Gotlieb Bloch increased the daily work norms for the workers. The workers protested. The management reduced food rations. The workers stopped working and intended to send a delegation to Warsaw. Fortunately, as a result of talks, the workers returned to work. The previous work norms were probably restored.

Within the current borders of Poland, the railway lines that were part of the former Warsaw – St. Petersburg Railway are railway lines: No. 6, 21 and 57. All along their entire length. The Białystok – Vilnius Railway Line is currently not used for rail traffic, except for trains from Grodno to Poland. The Lithuanian government is not interested in developing rail transport. The last discussions were held in 2020.

Written by Karol Placha Hetman