Katowice 2025-01-27

The Warsaw-Vienna Railway.

By 1860, there were already 200,000 km of railway lines in the world.

The Warsaw-Vienna Railway is one of the most frequently described railway lines in Poland. But in reality, these are journalistic descriptions, not to mention just any description. Only in old book publications is the Warsaw-Vienna Railway described in detail and carefully, and the authors put a lot of effort into their work.

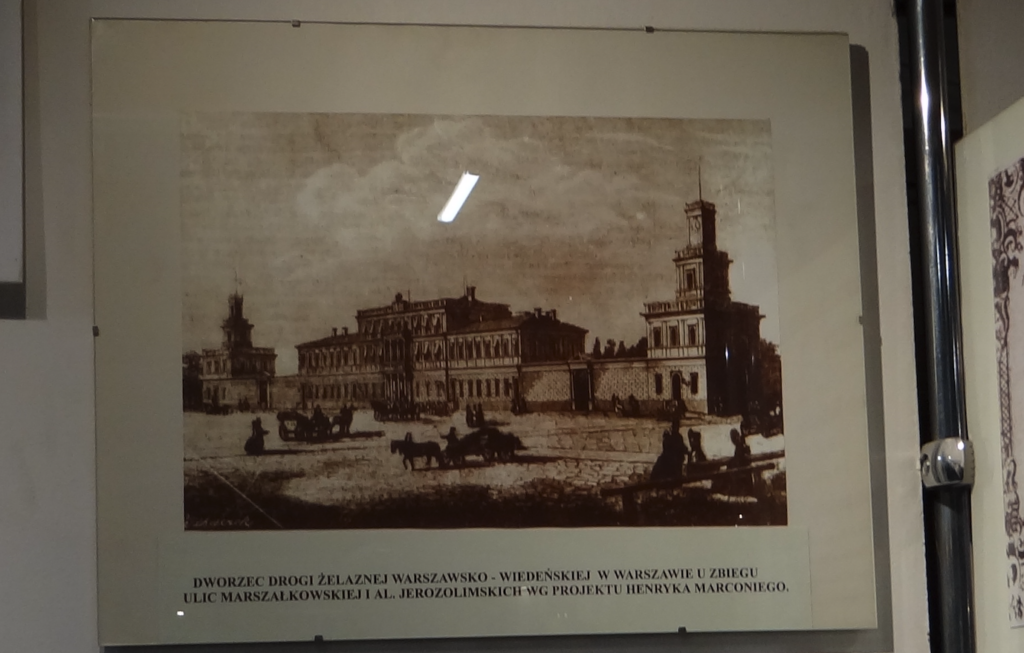

The originator and initiator of the construction of the Warsaw-Vienna Railway was Count Henryk Łubieński. Count Henryk Łubieński was born on July 11, 1793, in Prague. He was the son of Feliks and Tekla Teresa; a well-known landowner, count, financier, co-organizer of the Land Credit Society, member of the Sejm of the Kingdom of Poland, economic activist and industrialist. In 1835, he took the initiative to build a railway line connecting Warsaw with the Dąbrowa Basin. As a result, the Warsaw-Vienna Railway Society Joint-Stock Company was established. One of the founders of the Society was Piotr Antoni Steinkeller (1799-1854). Piotr Antoni Steinkeller developed mines and steelworks in the Dąbrowa Basin. Then he moved to Warsaw, where he was mainly involved in trade and the fashionable department stores of the time. He was one of the originators and original shareholders of the Warsaw-Vienna railway. In 1838, he initiated the establishment of the Warsaw-Vienna Railway Company. During the implementation of this investment, one of the shareholders went bankrupt; the Austrian company “Steineret Campanie” in Vienna, and the Company fell into debt and did not receive assistance from the tsarist government. The lack of funds caused the suspension of the works that had begun in November 1841. As a result, in May 1842, the Warsaw-Vienna Railway Company also went bankrupt. The railway was completed without the participation of Piotr Antoni Steinkeller. The shares of the Company were purchased by the Loan Bank of the Russian Empire.

The Warsaw-Vienna Railway was built according to the latest standards of the time. Numerous bridges, viaducts and railway stations were built, some of which have survived to this day and are historical monuments. The Warsaw-Vienna Railway was a symbol of modernity and technological development in the 19th century, and also contributed to the economic integration of Polish lands under the Russian partition, as well as the Austrian and Prussian partitions. The line was an impulse for economic development in the Kingdom of Poland, supporting trade, industry and agriculture.

The designer and chief engineer of the construction of the line was engineer Stanisław Wysocki. The construction of the route was divided into four sections. Section 1 Warsaw – Skierniewice, responsible engineer Konstanty Kamiński. Section 2 Skierniewice – Piotrków and Skierniewice – Łowicz, responsible engineer Jakub Szeffer. Section 3 Piotrków (currently Piotrków Trybunalski) – Częstochowa, responsible engineer Roman Pollini, and from 1844, engineer Adam Kranz. Branch 4 Częstochowa – Granica (Maczki), responsible engineer Franciszek Leszczyński.

Initially, it was considered to build a railway line with horse traction. However, information coming from the USA and Western Europe confirmed the greater benefits of steam traction.

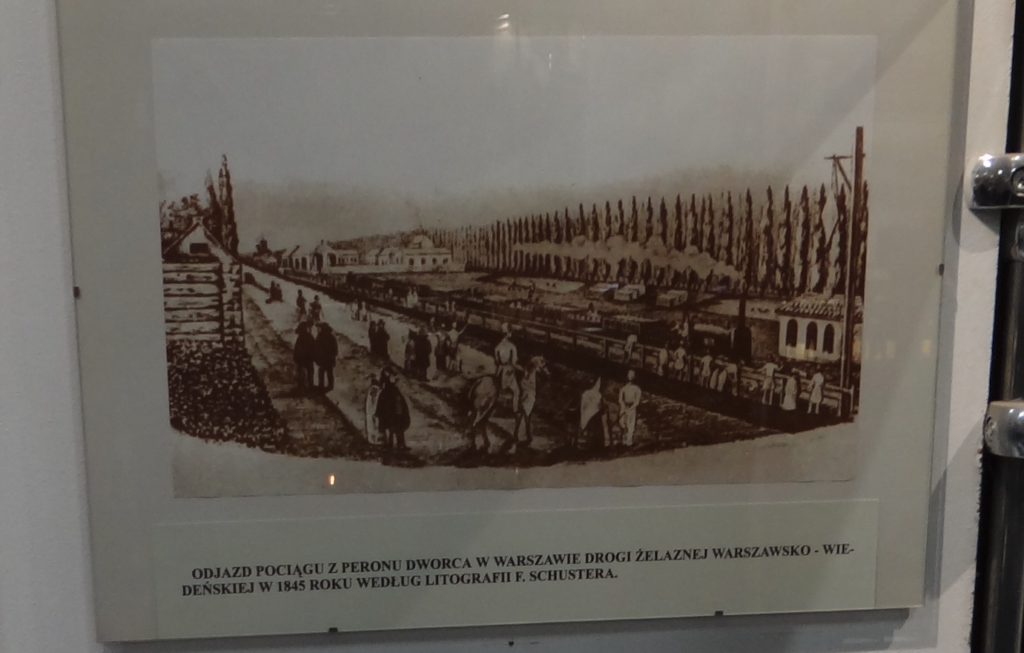

On July 4, 1843, the government of the Kingdom of Poland established the Warsaw-Vienna Railway Board and in 1844, work was started, financed by the Loan Bank of the Russian Empire. In November 1944, the first section of the line from Warsaw to Pruszków was completed. On November 28, 1844, the first train carrying the Russian governor of the Kingdom of Poland and his entourage passed through it. The one-way journey took 26 minutes, and the return 20 minutes. On June 15, 1845, the Warsaw – Grodzisk Mazowiecki section was launched in normal commercial traffic.

On June 15, 1845, the Warsaw – Grodzisk Mazowiecki section was launched. On October 15, 1845, the Grodzisk Mazowiecki – Skierniewice section was launched. On November 1, 1845, the Skierniewice – Rogów and Skierniewice – Łowicz sections were launched. On October 13, 1946, the Rogów – Piotrków section was launched. On December 13, 1946, the Piotrków – Częstochowa section was launched. On December 13, 1947, the Częstochowa – Ząbkowice section was launched. On April 15, 1848, the Ząbkowice – Granica (Maczki) section was launched. At that time, the Austrians launched the Szczakowa – Kraków route. A little earlier, the Prussians launched the Mysłowice station, which connected with the Szczakowa station.

On the Warsaw-Vienna Railway, stations and stops were built; Warsaw station and depot (locomotive shed), Włochy stop, Pruszków station, Browinów stop, Grodzisk Mazowiecki station and depot, Jaktorów stop, Ruda Guzowska (Żyrardów) station and depot, Radziłów station, Skierniewice station, depot and first railway junction, Łowicz station, Płyćwia station, Rogów station, Rokiciny station and depot, Baby station, Piotrków station and depot, Rozprza stop, Gorzkowice station, Radomsko station and depot, Widzów stop, Kłomnice station, Rudniki stop, Częstochowa station and depot, Poraj station, Myszków station, Zawiercie stop, Łazy station, Ząbkowice station, Strzemieszyce stop, Granica station.

The total length of the route was 327.60 km and had 27 stations and stops. The track was built with a rail gauge of 1435 mm. Importantly, at that time the Muscovites decided that the track width in the Muscovite state would be 1524 mm. On the Germanic map of Europe from 1849, the route was already drawn.

The Warsaw-Vienna Railway was the first railway line in the entire Moscow Empire. At the same time, it was the longest railway line built at one time in Europe. In 1845, 143,600 passengers and 143,300 hundredweight of goods were transported along the route. The Warsaw hundredweight weighs 64.8 kg. In 1845, the rolling stock consisted of 8 steam locomotives, which were fired with wood. The company had 58 passenger cars and 62 freight cars. In 1948, there were already 35 locomotives, 87 passenger cars and 312 freight cars. The locomotives were in the axle configuration: 1A1, B and B1. The locomotives were fired with wood, and the barrels were water tanks. From 1859, steam locomotives were fired with hard coal. For the education of railwaymen, the Technical Courses of the Warsaw-Vienna and Warsaw-Bydgoszcz Railway Company were funded, which were located in Warsaw. The Main Railway Workshops were funded in Warsaw, which employed 980 workers and were the largest factory in Warsaw. On October 1, 1875, the Technical School of the Warsaw-Vienna Railway was opened in Warsaw.

In 1850, two pairs of passenger trains traveled the entire route. There were separate passenger trains to Łowicz. From the Granica station there were passenger trains to Kraków and to Mysłowice. From Mysłowice there were direct trains to Vienna, Wrocław, Berlin and Hamburg. The passenger trains had freight cars in their compositions, in which animals could be transported, for example horses in covered wagons. In addition, there were freight trains. An example journey from Warsaw to Vienna looked like this: Warsaw, departure 7:30 a.m. Arrival at the Granica station at 6:00 p.m., i.e. travel time 9.5 hours. At 7:00 p.m. a train to Prussian Mysłowice departed. The following day, at 8:00 a.m. a train from Mysłowice to Vienna departed, and at 9:30 a train to Wrocław, Berlin and Hamburg. People going to Krakow spent the night at the Granica station, and at 7:00 a.m. the following day, they took a train to Krakow. Arrival in Krakow at 9:00 a.m., i.e. after two hours. On the Granica – Warsaw route, the evening train departed at 5:00 p.m. and stopped at the Częstochowa station, where passengers slept. The next day, the train set off at 6:30 a.m. and arrived in Warsaw at 2:00 p.m. The same was true for the evening train on the Warsaw – Granica route. At that time, there were already trains running at night on other routes. For example, from Mysłowice to Wrocław, the train departed at 8:30 p.m.

In 1859, the Ząbkowice – Sosnowiec connection was opened, and on to Katowice, which opened the first direct connection between the Muscovite brothers and the Germans (Russian partition and Prussian partition).

In 1862, the Łowicz – Aleksandrów Kujawski connection and further to Toruń was opened. This was the second connection between the Muscovite and Germanic brothers.

On November 19, 1865, the Koluszki – Łódź (currently Łódź Fabryczna) connection was created on a private initiative. Since 1857, the city authorities of Łódź and manufacturers had been postulating the construction of a connection to the Warsaw – Vienna Railway. Initially, the Moscow authorities were against it. Work on the construction of the Fabryczno – Łódź Railway did not begin until July 28, 1865. On November 18, 1865, track work on the construction of this 25.5-verst (slightly over 27 km) line was completely completed.

Along with technological progress, the Warsaw – Granica route was modernized. Pine sleepers were replaced with oak ones, which were subjected to preservation in autoclaves. In the 19th century, with the development of railways, the preservation of wooden railway sleepers became a significant problem, as they were exposed to rapid deterioration caused by weather conditions, moisture, fungi and insects. In order to extend their durability, various impregnation methods were used. One of the first and simplest methods was to impregnate the wood with wood tar, which was a by-product of the dry distillation process of wood. The tar acted as a barrier protecting the wood from moisture and attack by destructive organisms. In the mid-19th century, creosote, an oily product obtained from the distillation of hard coal, began to be used. Creosoting consisted of introducing this agent into the wood under pressure and temperature in special autoclaves. It was one of the most effective methods, which significantly extended the life of the sleepers, protecting them from fungi, insects and moisture. This process required the creation of tight chambers in which the wood was exposed to creosote at high temperature and pressure, which allowed for deep impregnation. In some cases, the sleepers were first dried and then immersed in hot tar. This process, although less effective than creosoting, provided some protection and was cheaper. There was also the Burnett method, which involved impregnating the wood with a solution of mercuric chloride (sublimate). It was effective in protecting the wood from rotting, but due to its toxicity and high cost, it was used on a limited scale. There was also the Kyan method. This was a method developed by John Howard Kyan, based on the use of zinc chloride as a preservative. The zinc chloride solution penetrated the wood and protected it from biological decay. By the end of the 19th century, creosoting had become the dominant method of preserving railway sleepers, because it provided the best results and was economical. The introduction of industrial impregnation methods allowed for a significant improvement in the durability of sleepers, which was crucial for the development of railway infrastructure.

Initially, only gravel or sand were used, which held the track well. However, as a result of heavy rainfall, the tracks were often washed away. Therefore, crushed stone was used, which turned out to be much better. Falling rain flowed through the stone base and did not wash it away.

Iron rails were replaced with steel rails. Iron is less durable and more susceptible to deformation and cracking under heavy loads. Iron rails wore out quickly, especially on curves and under the influence of wheel friction. Steel (which is an alloy of iron with carbon and other additives) has much better mechanical properties: it is harder, more resistant to abrasion and withstands greater dynamic loads. Thanks to this, steel rails could better withstand the increasing rail traffic and the weight of heavier trains. Steel rails lasted much longer, which reduced the frequency of track replacement and maintenance, which translated into lower operating costs. In the 19th century, with the invention of new methods of steel production, such as the Bessemer process (1855), steel became cheaper and easier to produce. Large-scale steel production allowed its use in railways, which had previously been economically unprofitable.

In the period 1860-1880, a second track was laid in stages from Warsaw to Ząbkowice. In 1890, the number of locomotives was 287, passenger cars 432, and freight cars 8,718. In 1913, the number of locomotives was 469, passenger cars 576, and freight cars 15,778.

The Warsaw-Vienna Railway was the most profitable. The railway became the basic means of exporting hard coal from the Dąbrowa Basin to the Prussians and textile products from Łódź to the poor Muscovite Empire.

In the period 1848-1857, the operation of the railway was in the hands of the Moscow treasury. In the period 1857-1864, the route was leased by a Germanic company. In the period 1864-1912, the route was in Polish hands. In 1912, the line was nationalized and converted to broad gauge. During the Great World War, the route was controlled by Muscovites, and then by Germans, who converted it to standard gauge. Since 1918, the route has been in the territory of the reborn Polish Republic, with a break caused by World War II, started by Germans and Muscovites.

Electrification of the route.

As early as the 1920s, at the request of the Government Commission, Professor Roman Podoski (1873-1954) developed a project for the electrification of railways in Poland, which included the electrification of the Warsaw Railway Junction and the electrification of the railway lines: Warsaw – Katowice, Katowice – Kraków and Warsaw – Przemyśl – Lviv. In 1921, at the request of Professor Roman Podoski, a decision was made that the electrification would be carried out with a 3 kV DC power supply. This was a major innovation, which was rarely used in other countries at the time. The advantage was the consumption of energy in the form of three-phase current from existing power plants, and not the need to build special power plants for the railway. Work temporarily slowed down due to other more urgent needs of the country. In 1928, a detailed schedule of works was adopted for the period 1928-1931. The schedule included the electrification of the cross-city line in Warsaw by November 1931.

In the period 1925–1927, thanks to the support of English capital, a line from Warsaw to Grodzisk Mazowiecki was built, managed by the carrier, on the basis of a concession for the section from Warsaw to Żyrardów, issued to Łódź industrialists, who were interested in the project and gave it up in favor of EKD (Electric Commuter Railway). This railway was made available to passengers on December 11, 1927. On the Warsaw-Vienna route, electrification began on the Grodzisk Mazowiecki – Żyrardów section as early as 1937. Further electrification of the line was interrupted by World War II. Pre-war projects provided for the electrification of the line on the section to Koluszki, but this was to take place after the electrification of the Warsaw junction, which was to be completed in 1941.

In the 1930s, the electrification of the Warsaw railway junction began. However, all plans were not realized due to the invasion of Poland by Germans and Muscovites. After World War II, the reconstruction of the ruined country began with enthusiasm. Unfortunately, the communists, who had been brought from Moscow, via Chełm and Lublin to Warsaw, took over power in Poland. The effects of this fact are still being felt today (2025). After the end of the war, the railway infrastructure was badly damaged by Germans and stolen by Muscovites. Due to the disastrous state of the economy, especially the electrical industry, it was impossible to start producing electric rolling stock in Poland. However, in 1948, plans were made for further electrification of railway lines, including the Coal Main Line from Chorzów to Tczew. However, the implementation of these works had to wait. In addition, the communists agreed to take the pro-German rolling stock and electric traction from Lower Silesia to Moscow. Despite this, the Warsaw railway junction was rebuilt.

After the end of the war, 36 E91 EZT units were put back into service, which were then redesignated E51, and then finally EW51. After the war, only one EL100 series locomotive was repaired, which after being repaired, worked from 1947 at the Warsaw Railway Junction. Then, from 1951, its designation was changed to E106, then to E01-01, and finally from 1959, it worked as EP01-01. After the war, none of the EL200 locomotives returned to service.

As early as 1945, an order was placed in the Swedish ASEA concern, which was founded in 1883 (and currently 2025, the ABB concern), for equipment for the Brwinów substation and two mobile substations mounted on rail vehicles. At the beginning of 1946, preliminary talks were held with ASEA regarding the conclusion of a credit agreement for the supply of electrotraction equipment for the Warsaw Railway Junction. Deliveries under the agreement concerned the complete equipment of six traction substations and section cabins as well as the equipment of the remote control control room of the electrical system. Additionally, the agreement included the supply of 44 three-car EZT series EW54 and eight electric locomotives series E150, with the axle arrangement Bo’Bo’. The agreement was signed on 16 April 1947. The first EZT were delivered to PKP in December 1950, and the rest in the period 1951-1953. The delivery of electric locomotives was completed in the period 1951-1952. In January 1948, fully assembled ASEA mobile substations were delivered, which were intended primarily as temporary replacements for the Warszawa Wschodnia and Miłosna substations, enabling the commencement of traffic on the Warszawa Wschodnia – Mińsk Mazowiecki route. Trains started running from Warszawa Wschodnia to Miłosna on February 3, 1948, and to Mińsk Mazowiecki on March 14, 1948.

At the turn of 1947 and 1948, there was an opportunity to purchase electric traction equipment in Great Britain, which was of great importance to PKP at that time, due to the pre-war technical conditions. Although Poland found itself among the countries dependent on Moscow after the war, the British did not liquidate the technical and commercial representation of the Contractors Committee for the Electrification of Polish Railways. At the beginning of 1949, an agreement was concluded with the Contractors Committee for the delivery of many parts necessary for the reconstruction of pre-war electric traction units and thirty sets of equipment for EZTs and eight for electric locomotives.

ET21 is the first Polish electric freight locomotive, which was mass-produced in the “PaFaWag” factory in Wrocław. 726 units were built. In 1955, in Poznań, based on the experience gained, an electric locomotive adapted to pull heavy freight trains was developed. The product was designated PaFaWag 3E, and subsequent versions 3E/1, 3E/1M. In PKP, the locomotive was designated ET21.

On June 23, 1949, the cross-city line was opened for rail traffic, which was rebuilt after it was blown up by the Germans in 1944, after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising.

From 1947, the electrification of the Grodzisk Mazowiecki – Żyrardów section began. The first electric train ran along this section on January 16, 1950.

From 1952, the pace of electrification of railway lines in Poland gained momentum. On March 14, 1952, the traction network was put into service on LK No. 21 Warszawa Wileńska – Zielonki and on LK No. 6 Zielonki – Tłuszcz. At the turn of 1957–1958, the electrification of LK No. 7 Otwock – Pilawa was completed.

On July 5, 1953, the Żyrardów – Skierniewice section was electrified. On April 30, 1954, the Skierniewice – Koluszki section was electrified, followed by the Koluszki – Łódź section. On September 10, 1954, the first electric train ran along the Warsaw – Łódź route (Łódź Fabryczna station).

In November 1955, the electrification of LK No. 1 was completed on the Piotrków Trybunalski – Częstochowa section. The first electric train entered Częstochowa station on January 21, 1956. On May 1, 1956, the first electric train ceremoniously entered Zawiercie station. On June 3, 1956, the LK No. 1 section to Łazy was ready. In 1957, the Łazy – Katowice – Gliwice section was already electrified. In this way, the entire Warsaw – Katowice – Gliwice route was electrified. As a result, the commercial speed of passenger trains increased from 40.8 km/h to 65.3 km/h, and of freight trains from 29 km/h to 49 km/h. Rail communication between Silesia and Warsaw is improving greatly. The saved hard coal could be directed to steam traction routes to Polish seaports.

Railway Line No. 1 Warsaw West – Katowice.

Currently, Railway Line No. 1 Warsaw West – Katowice is largely the former Warsaw – Vienna Railway. The length of LK No. 1 is 316.066 km. The line is double-track, electrified with 3 kV DC current, and the maximum speed is 160 km/h. The rail gauge is 1435 mm. The line runs meridionally. In the Polish railway system, it is the third alternative route that connects Silesia with Warsaw, and which complements CMK (via Opoczno, Włoszczowa) and LK No. 8 (via Radom, Kielce, Olkusz).

Written by Karol Placha Hetman