Kalisz 2025-03-14

Kalisz border crossing during the partitions of Poland.

It is worth describing the railway border crossing between the Germanic brothers and the Muscovites, near the city of Kalisz and the city of Ostrów Wielkopolski. This crossing operated in the period 1906-1914, i.e. for a relatively short time, because the Republic of Poland regained independence and both cities found themselves within the borders of Poland.

The city of Kalisz.

Kalisz is one of the oldest cities in Poland, whose history dates back to antiquity. As early as the 2nd century AD, Kalisz was mentioned by the Greek geographer Ptolemy as Calisia, which suggests that there was an important trade center here, on the amber route. In the Middle Ages, Kalisz became an important administrative and economic center. In 1257, the Duke of Greater Poland, Bolesław the Pious, granted the settlement city rights. In the 13th century, the city experienced economic development. In 1343, the Peace of Kalisz was signed in Kalisz between Poland and the Teutonic Knights. In the following centuries, Kalisz was repeatedly destroyed by wars, including during the Swedish invasion in the 17th century. There were also fires and plagues.

Then came the time of the partitions of Poland. Kalisz was first Prussian, because Prussia seized these lands during the Second Partition of Poland, and later Muscovite, because after the fall of Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna, Kalisz fell to the Muscovites, as part of the Kingdom of Poland. The Kingdom of Poland was completely dependent on Moscow. Despite this, in the 19th century, Kalisz became an important industrial and cultural center.

On November 15, 1902, the Warsaw-Kalisz Railway was launched. The Warsaw-Kaliska Railway route: Warszawa Kaliska – Błonie – Sochaczew – Łowicz Kaliski – Głowno – Stryków – Zgierz – Łódź Kaliska – Pabianice – Łask – Zduńska Wola – Sieradz – Błaszki – Opatówek – Kalisz.

The first train No. 1, from Warsaw to Kalisz, departed on November 15, 1902, at 8:00, with seven carriages. One more carriage was added in Zduńska Wola. The journey took 10 hours. The train arrived in Kalisz at around 18:00, welcomed by around 5,000 residents and a fire brigade orchestra. Train No. 2 from Kalisz to Warsaw also departed at 8:00, the same day. The train had 4 carriages and took 67 passengers. It is worth mentioning that the line originally had a single track, with passing loops built at the stations, and the average speed achieved at that time was around 25 km/h. This event was celebrated with a performance of Stanisław Moniuszko’s “Halka” at the Kalisz Theater.

Thanks to the railway, Kalisz began to develop dynamically. New industrial plants were built, and the city became more accessible to traders and investors.

The Kalisz railway station, built in the Art Nouveau style, was one of the most beautiful buildings of its kind in the region.

During the Great World War, the city was almost completely destroyed by Germanic troops in 1914. The destruction also affected the railway infrastructure, which had to be rebuilt in the following years. After reconstruction in the interwar period, Kalisz developed as a center of the textile industry and crafts.

During the Second World War, the city came under German occupation, and its population was subjected to repression. Trains with Poles departed from Kalisz station to concentration camps or forced labor in Germany.

After the war, Kalisz was rebuilt, and today it is an important economic, cultural and academic center in Greater Poland.

Despite the development of the railway, Kalisz has not developed to a satisfactory level for a city with a population of 93,137 (2023). The neighboring Ostrów Wielkopolski with a population of 70,982 (2022) has a much more developed railway network. The distance between the two cities is 24 km. This state of affairs has its source in history. Until 1918, Skalmierzyce, 8 km away from Kalisz, was the border between the Muscovite brothers (the Kingdom of Poland) and the Germans (the Prussian Partition). It was here, at the time at the junction of the village of Szczypiorno and the town of Skalmierzyce, that the border of the two partitions ran. This state of affairs influenced the differences between the two cities. For the Muscovites, the railway was just one of the weapons of war, and economic arguments were in the distant future. For the Prussians, on the other hand, the railway meant development and prosperity. The railway was the country’s communication backbone. In Prussia, there were already main routes that connected large cities and local lines. As early as 1842, there was a railway line from Wrocław to Oława.

What’s more, as early as 1862, Germanic manufacturers and merchants began to submit requests to St. Petersburg for the construction of a new railway line from Wrocław to Warsaw. A Committee for the Construction of Railways from Wrocław to Warsaw was even established. This was the time when the Warsaw-Bydgoszcz Railway was built (1862). The Muscovites did not agree. The proposals were repeated in 1868. Without effect. The construction of a railway junction in Ostrów Wielkopolski was to help the Muscovites take the initiative. In 1875, Ostrów Wielkopolski gained a railway connection with Poznań and Kluczbork. This line, which is used today, for example, to travel from Kalisz to the capital of Wielkopolska, became crucial in the development of Ostrów Wielkopolski.

The Muscovites had a different approach. For them, the area from Warsaw to Kalisz and Konin was to be a railway desert. Several subsequent initiatives to build a railway in the following years were rejected. Tensions in international relations were growing, and politicians did not hide their desire for war. It was not until 1898 that serious study work began for the construction of the railway. The Muscovites set several conditions; the track was to be 1524 mm wide. The line was to run from the Circular Line in Warsaw to Kalisz, without a connection at the border. The nationalization of the line was to take place after a maximum of 30 years. Only the Warsaw-Vienna Railway Company could meet these difficult conditions. On February 28, 1898, the Tsar signed a decision to start the investment, and on April 14, 1900, he approved the official technical designs for the construction.

The construction of a 1524 mm wide line was no problem for the Warsaw-Vienna Railway Company. The problem was the lack of rolling stock. Supervision of the construction of the line was entrusted to the Russian engineer Lipin. They also wanted to impose a chief construction engineer, to which the Society strongly protested. Ultimately, a rotten compromise was reached. The construction manager was the Muscovite engineer B.N. Kazin, and his deputy was the Society’s candidate, engineer Józef Prüffer. At that time, the Warsaw-Vienna Railway Company office was located in Warsaw at the Evangelical Square (currently Małachowski Square). It was headed by Baron Leopold Kronenberg Jr. The governor of Kalisz, senator Michał P. Daragan, and the general-governor of Warsaw, Prince Alexander Imeretynski, were deeply involved in the matter of the construction of the railway. The line was marked out through: Warsaw – Łódź – Kalisz – Skalmierzyce. Length 247 versts. A verst is an old Russian unit of length, equal to 1066.79 meters, in force since 1835.

Unexpectedly, the Germans refused a direct connection with the Prussian railways, the route was shortened to Kalisz. So the length was 236 versts. The total length of the tracks was to be 324 versts. The principle was adopted that the line was to pass without collision over other tracks and roads. Therefore, it was calculated that embankments would be on the length of 80% of the route. The aim was to guarantee unhindered transport of echelons. In reality, embankments were built on the length of about 20% of the line and many road crossings were built at the level of the tracks.

In total, on the distance Warsaw – Kalisz were built; 174 bridges and culverts, 17 crossings and viaducts, one tunnel and 11 railway stations. The Warsaw-Kalisz Railway line crossed 3 governorates and 9 counties.

The largest bridges were built on the Warta near Sieradz and on the Prosna near Kalisz. The bridge on the Prosna River was built as a three-span, truss bridge, with the carriageway placed on top. A similar bridge was built on the Ner River. This bridge had two spans, each 31.75 m long. The bridge on the Warta River near Sieradz was the longest on the Warsaw-Kalisz Railway. This bridge had five truss spans with the carriageway on top. There were two stone abutments and four stone pillars.

The planned cost of construction was 19,450,542 rubles. In reality, the construction cost 21,931,600 rubles. The increase in costs was associated with the purchase of land, where corruption was prevalent, and most of the money went to the commissioners.

New technical solutions, steel rails, new rail fastenings to the sleepers were used during construction. For the first time, 15 m long rails weighing 480 kg were used. For the first time, double sleepers and two-sleeper wide rail fastening elements were laid under the rail joints. Most of the solutions were developed by engineer Aleksander Wasiutyński.

For almost 50 years, there had been a Tsarist regulation that allowed land to be taken from owners for the construction of railway lines. It prohibited landowners from objecting to the takeover of land for the construction of railways. Sometimes even without compensation. Corruption was rampant. Commissioners-agents were appointed to take over land. Deeds of land takeover were written on ordinary heraldic paper, without paying the mandatory fees. Even land that was pledged in credit institutions was taken over. The reports did not show any conflicts during the buyout, because all matters were settled by request, threat and bribe. The applicable fee schedules were interpreted at the discretion of the commissioner-agent. According to reports, compensation for the enfranchised lands was relatively high, but most of the money went into the private pockets of the commissioners-agents. The wronged peasants were unable to defend their interests in the tsarist institutions. The defrauded peasants often hired themselves out to work on the construction of railways. However, a lot of land was also taken over on the basis of an agreement and for a fee.

The workers were assigned to units called “Artele” (артель). There was no specified number of workers in a given unit. The head of the unit was the organizer of the works, who had under him the starostas of the artals, and they already managed the workers. In the event of a worker’s illness, 40 silver kopecks were deducted from his salary daily (30 for food and 10 for medicine). In the event of a worker’s death, his debt was paid by the entire artel. Collective responsibility was in force. The workers lived in barracks without sanitary facilities, which is why smallpox, cholera, plague and other diseases were spreading. There was a high mortality rate. The day lasted over 12 hours. Sunday was a day off from work.

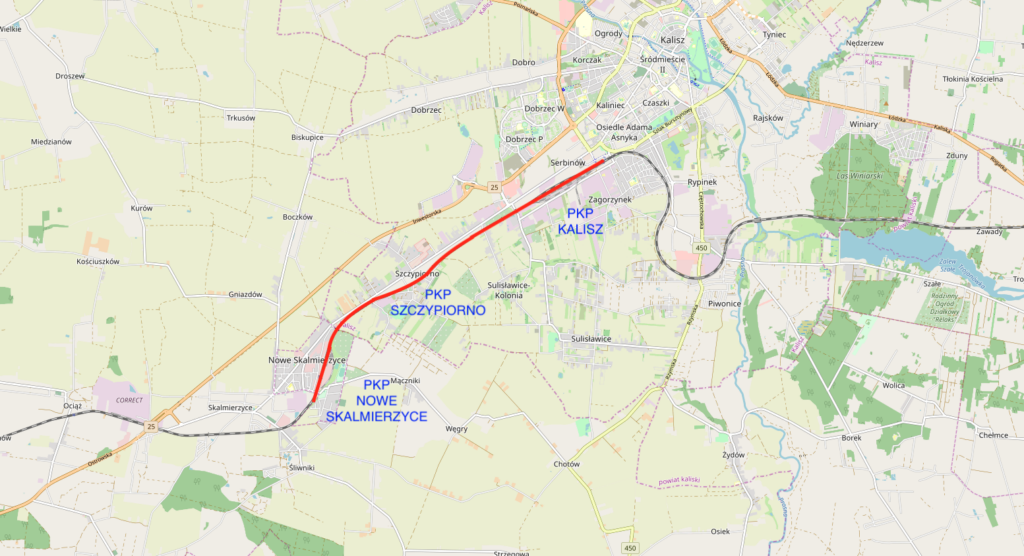

The Warsaw-Kalisz Railway Route: Warsaw Kaliska – Błonie – Sochaczew – Łowicz Kaliski – Głowno – Stryków – Zgierz – Łódź Kaliska – Pabianice – Łask – Zduńska Wola – Sieradz – Błaszki – Opatówek – Kalisz. A cross-border section of tracks with a standard gauge of 1435 mm was built at the western border of the Kingdom of Poland, which connected Kalisz and Skalmierzyce (currently Nowe Skalmierzyce). But we wrote about that below. 11 railway stations were built on the line. The stations in Warsaw, Łódź and Kalisz were built according to individual designs. The Warsaw Kaliska station, architect Józef Huss, put into operation in 1902, was demolished in 1915 and not rebuilt. The Łódź Kaliska station, architect Czesław Domaniewski, put into operation in 1902, demolished in 1982. Kalisz Station, architect Czesław Domaniewski, put into operation in 1905, demolished in 1914 and rebuilt. The remaining 8 stations were built according to one design in two variants. The stations are single-storey with large windows with a semicircular ending. The trackkeepers’ cottages were built according to one design. Disputes between the brothers led to the lack of a common connection between the Prussian Railway and the Kalisz Railway. The station built in Kalisz was intended to be an island station. On one side there were to be broad gauges, and on the other standard gauges. However, there was no agreement on a common border station. Finally, on 6 December 1904, an intergovernmental agreement was signed in Berlin, under which the Kalisz line was extended to Skalmierzyce. On the other side, standard gauges were added, 1435 mm. The broad gauge reached Skalmierzyce, and the standard gauge reached Kalisz. At both stations and at Szczypiorno station, goods were reloaded. To facilitate reloading, one track was higher, and the other one was lower next to it. Goods were reloaded from wagons on the higher track to wagons on the lower track. Two customs chambers were established for passenger traffic; the Germanic Skalmierzyce, the Moscow Kalisz. Trains with passengers from the Western side reached Kalisz, and trains from the Eastern side reached Skalmierzyce. The passage between platforms was treated as crossing the border. There were fences, gates and customs guards. Regular traffic began on October 28, 1906. At Skalmierzyce station, the Germans built an impressive brick station. The station was to make passengers aware of the power of the Germans. The station exists to this day (2025). The name Nowe Skalmierzyce has been in use since 1967.

The first talks between the brothers; Muscovites and Germans, on the location of the border station on the constructed Warsaw-Kalisz Railway took place at the turn of December 1900 and January 1901, in Poznań. In May 1901, further talks began. This time in Kalisz. The Muscovites pushed for the location of the border station in Kalisz. The Germans stood by the location in Szczypiorno. There was even a proposal for a joint station on Prussian territory next to Ostrów Wielkopolski. The focus was on three locations: Kalisz, Szczypiorno, Skalmierzyce. The problem was that the distance from Kalisz to Skalmierzyce is 8 km, unacceptable to the Germans. There was no agreement. Another meeting was held in Aleksandrów (Kujawski) (Warsaw-Bydgoszcz Railway) on January 29, 1902. There was still no compromise. The Muscovites were not interested in developing the western part of the Kingdom of Poland. That is why they demanded that the Germans modernize their Zbąszyń-Leszno-Ostrów-Skalmierzyce route for express trains. The Prussian side still counted on good trade. That is why the Prussians proposed that they themselves build the Skalmierzyce border station. There was still no agreement. It was expected that transport across the border would be carried out by carriages and horse-drawn carts.

The Prussian government decided to buy the local government initiative to build the Ostrów-Skalmierzyce Railway. The local government society was established in December 1900 and had all the necessary permits. The number of tracks under construction changed from one to two. Work began in 1904. This short line was put into service on October 1, 1906.

Unexpectedly, the brothers found common ground. This was related to their common interests in the Far East. From February 8, 1904, to September 5, 1905, the Japanese-Muscovite war was fought. The Muscovites lost decisively; both on land and at sea. Japan gained large areas and world importance. Since the issue was colonization, all of Western Europe was on the Muscovite side. European calculations of wrongs had no significance here.

Talks on the border crossing near Kalisz, interrupted in January 1902, were resumed in 1904, and a compromise was reached in September 1904. On December 6, 1906, an international agreement was signed in Berlin. It was ratified on January 3, 1907, when the border crossing was already in operation. According to the arrangements, the border crossing included three stations; Kalisz, Szczypiorno and Skalmierzyce, which was a unique event. On the Kalisz – Skalmierzyce section, normal and wide tracks were laid. It was planned to lay second tracks, of any gauge. In Skalmierzyce, a border bridge was built over the tracks, which assumed the laying of four tracks.

All three stations were built as island stations. At the transshipment points, some tracks were higher, and others were lower. Goods were reloaded from wagons placed on higher tracks to wagons placed lower, which made reloading easier. A system of changing wagon bogies was not used. There were several reasons. Firstly, the Muscovite wagons had a different gauge, and most of them did not have pneumatic brakes. Secondly, the station workers were afraid of losing their jobs. In 1910, there were about 200 of them working at Szczypiorno station, and about 250 in Skalmierzyce. Wagon scales were installed in Skalmierzyce and Szczypiorno. The entire route between Kalisz – Szczypiorno – Skalmierzyce was lit and fenced. The military kept watch.

Officially, freight and passenger traffic was opened on October 28, 1906. Muscovite passenger trains stopped at Kalisz station and after a stopover, they went to Skalmierzyce. Passengers got off and went to the customs chamber or to the waiting room-restaurant. After customs clearance, they went to the other side of the station and boarded Prussian trains. On the western side, Prussian trains stopped in Skalmierzyce. Prussian locomotives were detached and Russian standard-gauge locomotives were attached to the trains. The conductor’s team was changed to a Russian one, consisting of only the manager and his assistant. Tickets and documents were not checked. The train set off for Kalisz and here there was customs clearance, passport control and a change to Russian wagons, on wide tracks. There were many soldiers at the station, who maintained order and had the right to check passengers. Prussian passenger wagons returned empty to Skalmierzyce. In passenger traffic, no train stopped in Szczypiorno. Prussian steam locomotives were serviced only in Skalmierzyce. Prussian freight cars, on the other hand, travelled to transshipment points at one of the three stations, just like Muscovite cars. At all three stations, the Muscovites knew each other well; both the customs officers and the railway workers. At Skalmierzyce station, the Prussian customs officers and railway workers knew the Moscow staff who worked at Skalmierzyce well. There were permanent teams of steam engines, teams of conductors, auditors and customs officers. Changes of personnel were very rare and were signalled in advance.

In time, to make things easier, two pairs of freight trains were organised on the Kalisz – Ostrów Wielkopolski line, on standard tracks. Goods loaded at these stations were already customs cleared and the trains covered this route without stopping. The Skalmierzyce stations were serviced by two broad-gauge locomotives belonging to the Muscovites. In 1907, at this station, the Prussians had their own broad-gauge locomotive, a T3 type tank locomotive.

In the Kingdom of Poland, the Skalmierzyce railway border crossings, in terms of goods turnover were comparable: Kalisz, Aleksandrów Kujawski, Sosnowiec, Granica, Grajewo, Mława. On the other hand, Kalisz and Skalmierzyce were first in terms of passenger and road traffic. This was related to the smuggling of small goods, which did not exist in the Kingdom of Poland. There were initiatives to build a horse tram on the Kalisz – Ostrów Wielkopolski section. Narrow-gauge rails were planned to be laid in a road. The plan was not implemented, because electric trams were launched in Ostrów Wielkopolski. On November 11, 1918, the Kalisz station was occupied by the Poles. On May 27, 1919, at the Kalisz station, Józef Piłsudski met with General Józef Dowbor Muśnicki and General Józef Haller. In 1923, the President of the Republic of Poland Stanisław Wojciechowski visited Kalisz twice. In 1938, the relics of Saint Andrew Bobola passed through the Kalisz station and stopped here on their way from Rome to Warsaw (to pay homage), and then the remains of General Edmund Taczanowski. General Edmund Taczanowski is remembered by the people of Wielkopolska primarily as one of the commanders of the January Uprising of 1863-1864.

The Second World War spared the station, and for the next decades it hardly changed. During the German occupation, the Kalisz station was the scene of deportations of hundreds of Poles to concentration camps and to forced labor in the Reich.

In 1956, plans were made to reconstruct the Kalisz junction. It was planned to move the passenger station to the area of today’s Chmielnik district, and the freight station between Winiary and Opatówek. It was planned to eliminate the pseudo-serpentine section; Rypinek. A new line to Pleszew was also planned. Lines were to be built to Inowrocław via Konin and to Częstochowa via Wieluń. These plans were already thrown in the bin in 1957. During the PRL period, the station housed the “Kolejowa” restaurant belonging to “Społem”, where you could eat bigos or tripe, even at night, when other restaurants were closed. Until recently, there was also a RUCH kiosk.

Currently, it is easy to notice that the station in Ostrów Wielkopolski is much more extensive than the station in Kalisz. Ostrów Wielkopolski accepts trains from as many as five directions; Poznań, Łódź (Kalisz), Katowice, Wrocław, Leszno. Kalisz has only two directions, because it is a through station. Looking at the timetables from both stations and comparing them with each other, you can also see the differences in the number of all connections provided by both stations. The station in Ostrów Wielkopolski is practically alive all the time. Trains stop here both during the day and at night. Currently, Kalisz station is part of a transfer center.

A new railway line as part of the CPK Program could be a chance for Kalisz. Then there would be a new route; Poznań – Kalisz – Sieradz, as part of spoke No. 9. Unfortunately, since December 13, 2023, Poland has been governed by the December 13 coalition (Prime Minister Tusk), which abolished this program. Let us recall that in 2007, after the parliamentary elections, talks began on the construction of a high-speed railway in our country. This topic also appeared in the parliamentary exposé of then Prime Minister Tusk. “My government will urgently complete work on the study of high-speed railways in order to move from the study phase to the implementation phase during this term of office,” said the Prime Minister at the time. A year later, the PO-PSL coalition government adopted a program for the construction of the “igrka” line. Its name comes from the shape it was to take; the fork was planned to be built near Nowe Skalmierzyce. Well. Promises cost nothing.

On November 18, 2022, at 1:00 p.m., in the Kalisz Railway Station Hall, a concert of the OSP Dobrzec Brass Band conducted by Jacek Konopczyński took place. The performance was to celebrate the 120th anniversary of the railway in Kalisz. There were also exhibitions: photography and railway modeling.

Kalisz Station.

Kalisz Station was opened for use on November 15, 1902. The station was built in 1905, according to the design of the architect Czesław Domaniewski. It housed: a post office, customs office, restaurant, ticket and luggage offices. On one side of the station there were wide tracks. From 1906, on the other side, normal tracks were laid westward. As a result, the station was an island station. Mainly sandstone was used for construction. In 1914, retreating Muscovites burned down the Kalisz station and destroyed the railway bridge over the Prosna in Piwonice. Over the course of its history, the station was rebuilt several times. The current style is modernist.

A water tower was erected at the station, which was destroyed in 1914 by Prussian artillery fire.

The station was rebuilt in 1920. The Kalisz inscription was placed on the front of the building. The Kalisz inscription was no longer written in Cyrillic. The wide tracks were removed and a huge station square was built in their place.

During the German occupation (1941), a large brick water tower was built. The Germans built water towers of this type in Katowice and Toruń. The tower in Kalisz is used as a base for mobile phone antennas and for climbing.

The current owner of the station is the PKP company, and the owner of the station is the PKP PLK company. There is a ticket office in the station building. The station has the status of a provincial station. For over 10 years, passenger exchange at the station has been over 1,500 people per day. Except for the period of the Chinese virus pandemic. In 2023, the station served 1,800 passengers per day.

The station is located on LK No. 14 Łódź Kaliska – Tuplice (western border of Poland). There are two platforms and two platform edges at the station.

The last renovation of the station was carried out in 2014-2015. The facility was adapted to the needs of disabled people. The window and door joinery and installations were replaced. The roof was renovated. The external elevation was renovated. The grand opening took place on November 27, 2015.

Kalisz Szczypiorno.

Szczypiorno station had a very short history. In its original form, it operated in the period 1906-1914. The station did not handle passenger traffic. A small station building, several warehouses and social rooms for railway workers and customs officers were built between the wide and normal tracks. There was a locomotive shed for two steam locomotives and a water tower. There was a crossing guardhouse, a track (maintenance) building and a switchman’s building. A residential block for railway families was also built. There was also a large residential block for workers from the transshipment artel, who had their baths in a separate building.

When the Great World War broke out, in the autumn of 1914, the broad gauge tracks were converted to normal gauge tracks. Szczypiorno station became a place where rails were acquired for the repair of damaged tracks. In 1915, a prisoner-of-war camp was organised, using the fenced areas. Only two main tracks and a lot of land remained from the former Szczypiorno station. During the Second Polish Republic, the station area was occupied by the Polish Army as a depot. In 1925, a passenger stop was opened. After the Second World War, the Polish Army again occupied the warehouses. In 1946, the army transferred the warehouses to a state-owned agricultural enterprise. In 1947, the sidings and the branch post were reopened. At the Szczypiorno stop, a waiting room and a ticket office were opened in a barrack. However, in 50 years, the station building was already significantly damaged and was demolished. However, the warehouses of the agricultural company were gradually renovated. The company had its own shunting locomotive. In 1958, PKP renovated all the tracks. In total, it was about 3,000 m of tracks. In 1961, next to the station, warehouses of the Poznań Construction Materials Central were built, to which sidings were connected.

In December 1975, the electrification of the KL No. 14 Zduńska Wola – Ostrów Wielkopolski section was completed. At that time, the SRK devices were modernized. A brick stop was built in 1977. In 1977, the name of the stop was changed to Kalisz Szczypiorno. In 1984, the SRK devices were replaced with relay ones. Traffic lights were installed. In 1992, the branch post was liquidated. The side posts to the companies were reclassified as track posts. The signal box (on the leg) was liquidated in 1994. The control of the main turnouts was moved to the Kalisz station. However, the companies served by the sidings stopped using them. In 2003, the sidings were closed. In 2008, the turnouts on the track tracks were liquidated. Both companies at the Szczypiorno station; Agroma and Centrala Materiały Budowlanych moved out and sold the land.

One warehouse, a pumping station building and apartment blocks have survived to this day. There are also new warehouses, which are serviced by road transport. The rail-road crossings of the former sidings have been eliminated. Local trains of the PolRegio carrier and Koleje Wielkopolskie stop at the stop, which has an island platform. The crossing is at the level of the tracks. There is a brick bus shelter on the platform. The platform is low, has a surface made of pavement tiles and is lit. The middle of the platform is a green square. The stop is accessed by paths. Numerous companies have their headquarters on the former station level. The rail crossings along the streets; Sąsiedzka and Starowiejska are automatically guarded. The historic viaduct with a road under the tracks along Gościnna Street has been preserved. The Catholic chapel dedicated to St. Barbara was built in 1925.

Nowe Skalmierzyce Station.

The station was built in the Germanic neo-Gothic style, as an expression of Prussian power and more closely resembles a pagan cathedral. The building was built on the plan of an elongated rectangle, measuring about 100 m x 24 m. On the main facade of the building, in medallions, there are only missing portraits of prominent Germanic genocidal murderers. Its shape finds no reference to other stations in western Poland. We can find some analogies in the construction in Masuria. The station was built of red brick, as an island station. This type of station was very popular with the Prussians in the second half of the 19th century. Such stations were built in Poznań, Piła, Leszno and Jarocin. The station in Skalmierzyce received two large projections at the front, with narrow high windows. Between the projections there was the main entrance and a window symmetrical to it. The entrance was roofed. The whole is crowned by a high tower placed centrally, in the base of which there was an analog clock; a bit small. The railway sign was placed on the top of the tower; a wheel and two wings. The whole thing was covered with glazed ceramic roof tiles; red and green. Inside the station there were two halls, waiting rooms-restaurants; one for 1st and 2nd class passengers, and the other for 3rd and 4th class passengers. Each hall had an area of about 180 m2. The first hall was decorated with palm trees, crystal chandeliers and marble sculptures on the walls. The second, of the same size, was modestly furnished. There was one customs and passport control hall. Its area was about 840 m2 (according to the plan it was 836.81 m2), and the height reached 9 m. The main corridor ran along the western part of the station and was up to 4 m high. There were ticket and luggage offices, currency exchange offices, a hairdresser, restaurants. The upper part of the station was occupied by the railway and customs services. There were also apartments. The building had central heating, gas lighting, a telephone and a telegraph. Roofs were added along the side walls of the station, on the outside. An impressive post office building was also built on the station square. A representative cobbled street led to the station square, passing over the western tracks.

Construction work on the station began in November 1905. A year later, the station building was ready. The work was carried out by masons from Ostrów Wielkopolski. A brick water tower was built at the station in its north-western part (1913). A housing estate with apartment blocks was built to the west of the station. A large signal box was erected at the viaduct over the tracks, which still exists today, “Sk”.

In 1913, a meeting of brothers took place at the station; Emperor Wilhelm II and Tsar Nicholas II.

Already in the reborn Poland, in 1923, large wagon workshops were built on the station premises. There was a forge, carpentry shop and warehouses. In the 20 years, the reconstruction of the interior of the station began to adapt it to the changed needs. High halls were divided by ceilings. Staircases were relocated. Water and sewage systems were installed, and as a result, toilets. Electrical installations were installed.

At the end of 2015, the facility was taken over by the Municipality and City of Nowe Skalmierzyce, and in 2017, it was entered on the list of monuments. The last renovation was carried out in the period 2016-2019. A brick bunker has been preserved near the platforms.

Currently (2025) the Nowe Skalmierzyce station serves 21 passenger trains per day. You can go to the stations; Kalisz, Leszno, Łódź Kaliska, Ostrów Wielkopolski, Poznań, Warszawa Wschodnia. Carriers are; PolRegio and Koleje Wielkopolskie.

Written by Karol Placha Hetman