Kraków 2025-03-04

Ivangorod-Dąbrowa Railway. 1885

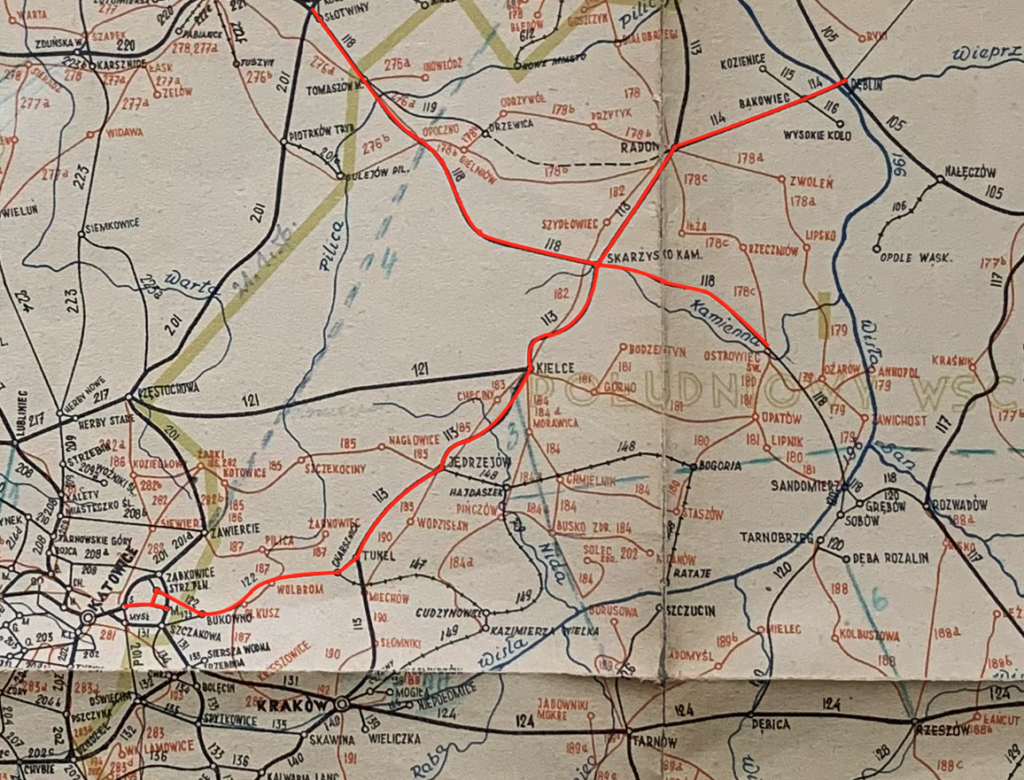

The development of railways in the Kingdom of Poland, as in the Muscovite state, was hampered by Moscow. The issuance of concessions lasted for a dozen or so, and sometimes over 20 years. Only on July 10, 1881, did the tsarist government issue a concession for the construction of the Ivangorod-Dąbrowska Railway (Ивангородо-Домбровская железная дорога). In that year (1881) a society of domestic capitalists was formed in Warsaw, under the name of the “Ivanogród – Dąbrowska Railway Company”, for the construction and operation of the aforementioned road. The beginning of the road was designated at the Ivanogród (Dęblin) station on the Vistula Railway. The new line was to run: Ivanogród – Radom – Bzin (Skarżysko Kamienna since 1897) – Kielce – Dąbrowa. Additionally, there were to be branches from the Bzin station to Koluszki and to Bodzechów, near Ostrowiec. It was also ordered to build a rail-road bridge over the Vistula River, at the height of Ivanogród. The board consisted of: landowners; Margrave Zygmunt Wielopolski, Count Tomasz Zamojski, Stanisław Karski, August Ostrowski and Władysław Laski. There were also industrialists; Karol Scheibler, Wilhelm Rau and Leon Lowenstein and bankers; Jan Gottlieb Bloch and Leon Goldstandt. Initially, the Society paid the Tsarist government 250,000 rubles (such Russian currency), which sum was raised to the required 1 million rubles. The line was to be completed within 3.5 years. The concession was to be granted for 50 years, and after that time the line and rolling stock were to become the property of the Moscow state treasury. The Muscovites did not meet this condition. The investment was valued at 27,229,349 credit rubles.

Let us remember that a total of 16 entities applied for the concession for the Ivano-Frankivsk – Dąbrowa line, but only the Warsaw – Vienna Railway Company counted. But it was a thoroughly Polish company, which did not suit the Moscow state. The offer of the Warsaw – Vienna Railway Company was 1 million rubles cheaper. In addition, the company, in the signed documents, had priority in granting concessions for the construction and operation of other railway lines. But the Muscovites did not respect this right. The protests were effectively neutralized, among others, by Jan Gottlieb Bloch, who recalled the insurrectionist past of the banker Leopold Stanisław Kronenberg and eliminated him from his position.

The following were appointed to the Society’s board by the shareholders: Margrave Zygmunt Wielopolski (president), Jan Gottlieb Bloch (vice president), Stanisław Karski, Leon Goldstandt, Wilhelm Rau. On August 10, 1882, the following were also appointed: Władysław Laski, August Ostrowski, Count Ryszard Potocki, Andrzej Nagórny. Jan Gottlieb Bloch supervised the finances. Engineers Izmailow and Cieszkowski supervised the technical matters. An Italian specialist, Forradini, was employed to supervise the construction of bridges. The bridgeheads and pillars were built by Italian stonemasons.

The Ivanogród – Dąbrowska Railway was divided into three sections: 1 Ivanogród – Bzin (91 versts. 1 verst = 1.0668 km). 2 Bzin – Dąbrowa (188 versts). 3 Koluszki – Bodzechów (154 versts). In total, this is 433 versts, or 461.924 km.

It was one of the longest railway lines in the Kingdom of Poland and in the entire Muscovite state. The line allowed for the relief of the Warsaw railway junction. At the same time, it relieved the Warsaw-Vienna Railway. Without a doubt, this line was the most difficult to build. It ran through areas that were already well industrialized and populated, but above all through the area of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains. The line required the construction of over 400 bridges and culverts. Many kilometers of ravines and embankments had to be built, with a depth of 6-9 fathoms. A fathom is an English measure of length; 1 fathom is 6 feet, or 1.892 m. The cuttings had to be made in limestone, quartzite and sandstone. About 1,000 poods of dynamite were used in the mining works. A pood is an old Russian unit of weight. 1 pood = 16.38 kg = 40 pounds = 1,280 luts. From Suchedniów to Chęciny, for a length of 60 versts, the line constantly runs in arcs without straight sections, sometimes rising, sometimes falling. In the vicinity of the Zagnańsk station, for a length of 1 verst, three retaining walls were built, which are 3 fathoms high.

Italian stonemasons were brought in to build the bridges. The abutments and pillars of the long bridges were made of granite or sandstone. The steel bridges were made according to the latest solutions, with a riveted construction. The longest bridge, 1,400 feet long, was made in the Dutch system. The individual elements were made in the Ostrowiec Steelworks and in other plants in the Kingdom of Poland. The bridge has two abutments and 4 pillars, which were made of granite. A similar bridge was built on the Pilica River near Tomaszów, 521 feet long. A wooden bridge was built on the Duża Nida River, 420 feet long. Even more important bridges were built; On the Kamionna River near Ostrowiec, 210 feet long. Near Bzin, a bridge 140 feet long. On the Czarna Nida near Chęciny, 175 feet long. On the Węglanka near Opoczno, 140 feet long. At Dzrewiczka near Końskie, 105 feet long. At Mierzawa near Sędziszów, 84 feet long. At Radomka near Radom, 49 feet long. At Rozbójnica near Kielce, 49 feet long.

The layout of the railway resembles a crossroads of lines from four directions. All branches converge in Bzina (Skarżysko Kamienna), Końskie County, Radom Governorate.

At that time, railway stations were in four categories. However, all brick stations were planned for this route, unlike on the Warsaw-Terespol line, or Warsaw-Petersburg, where wooden stations were built. The stations were two-storey, except for the stations in Ivanogród and Koluszki. On the Iwanogród – Dąbrowa section, the following stations were planned: Iwanogród, Garbatka, Jedlina, Radom, Jastrząb, Bzin, Suchedniów, Zagnańsk, Kielce, Chęciny, Jędrzejów, Sędziszów, Miechów, Wolbrom, Olkusz, Sławków, Strzemieszyce, Dąbrowa. In the Dąbrowa Basin, it was decided to extend broad gauge tracks to: Dąbrowa station, the Bankowa steelworks and the Granica (Maczki) station. On the western section, the following stations were built: Koluszki, Tomaszów, Opoczno, Końskie, Niekłań. On the eastern line, the following stations were built: Wierzbnik, Kunów, Ostrowiec, Bodzechów. In 1885, it was additionally agreed that there would be a joint station with the Austrian railways. From the Sławków station, a 6-verst long line was built to the border village of Borki, opposite the Szczakowa station, which belongs to the Northern Ferdynand road. A second branch was also planned from Strzemieszyce station to the village of Modrzejowa, 21 versts long, to connect with the Prussian railway network in Silesia.

The tunnel under Biała Góra.

An interesting element of the line is the unnecessary railway tunnels on the route near Miechów. This was a stupid requirement of the Muscovites, whose aim was to stop a possible Western invasion of the Muscovite Empire. In the initial plans, the tunnels were to be 2,457 English feet long, 27 English feet high, 17 English feet wide. Over 3,500,000 bricks were used to build the tunnels.

At a distance of 10 km from Miechów station, towards Warsaw, there is a railway tunnel under Biała Góra hill (elevation 416 m). The tunnel is an element of the infrastructure of route No. 8, Warsaw – Kraków. The tunnel was built solely for Moscow’s military purposes. The Biała Góra hill is relatively small, and bypassing it would not be a problem, as evidenced by the construction of the broad-gauge LHS line in the 1970s, which runs partly parallel to route No. 8. The tunnel was an element of the Iwangorodsko-Dąbrowska route. The railway tunnel was intended by the designers as an element that, in the event of a war with Prussia or Austria-Hungary, could be blown up and make an enemy attack more difficult.

In 1882, construction of the first of two tunnels began. A brickyard was opened for construction purposes, because the interior of the tunnel was lined with a brick wall. On July 27, 1883, the teams shaking the tunnel from both sides met. The tunnel was put into operation on January 25, 1885. The length of the tunnel is 764 m. Wide tracks were laid in the tunnel. In the tunnel, every 80 meters, small chambers (niches) were built for railway workers to hide from the approaching train. There are also two chambers in the shape of the letter “T” for strategic and storage purposes. There is a significant slope in the tunnel towards the north, which is 8 per mille. The tunnel runs almost in a straight line. The entrances to the tunnel were bricked up and provided with the dates 1882 – 1884, which means the beginning and end of the construction of the first tunnel. The farms that were on the hill were liquidated, the population was evicted, and the fields were afforested. It was the first railway tunnel in the Kingdom of Poland. Currently, the border of the Kozłów commune and the Charsznica commune runs through the hill. The construction of the tunnel was very expensive, so the parallel excavation of the second tunnel did not begin until 1910, and it was put into operation in 1912. The second tunnel is 40 m away from the first one. Its length is the same as the first tunnel, i.e. 764 m. Other data indicate a length of 768 m. The nearby Tunel railway station owes its name to the facility.

In 1914, according to the plan, the tunnels were blown up. They were rebuilt in Independent Poland, in 1920. In 1934, a line was built from the Tunel station (Uniejów Rędziny) through Miechów, Słomniki to Kraków. In this situation, the importance of the route from Radom and Kielce increased. Currently, the route on the Tunel – Sosnowiec Główny section is marked Line No. 62. During the Defensive War in 1939, the tunnel was not destroyed. However, it was blown up in 1945 by the retreating German army. The tunnels were rebuilt in 1945.

In 2005, the tunnels were given the names “August”, the western tunnel (previously “Ferdynand”) and “Włodzimierz”, the eastern tunnel (previously “Jan”). A twin tunnel was to be built near Suchedniów. It was not built because the Great World War began.

Railway stations.

The stations were built as brick ones. Many of them were equipped with waterworks, as for example in Bzin, Radom and Kielce. Railway workshops were built in Radom, where three large halls were built for them. In Bzin a locomotive shed was built, which housed 22 steam locomotives. The central office of the Ivanogródzko-Dąbrowska Railway was placed in Radom, and the management office was located in Warsaw on Marszałkowska Street.

For the construction of the line, 3,500 landed properties, which were in the possession of 3,000 owners, were seized. This was over half a million square feet. Most of the land was acquired by voluntary agreement, without resorting to the law of expropriation. This was a much higher level of civilization than at the time of the expropriations for the Warsaw-Petersburg Railway or the Warsaw-Terespol Railway. Large sections run through forests owned by the Moscow government. The area taken over by the railway was very diverse. The arable land was of various classes, from very fertile to sands and clays. There were also rocky mountains, most of which had to be avoided. As a result, it was the highest railway line in the Moscow state. In addition, the line runs through numerous towns; villages and cities, where one could find people willing to work on the construction of the line or work on the railway. The Świętokrzyskie Mountains are currently (2025) the lowest and oldest mountains in Poland. Their height in elevation ranges from 134 m to 614 m and it was a difficult area to run a railway line. In the vicinity of Chęciny we have rich deposits of multi-colored marble. On the other hand, the areas of Sandomierz, Opatów, Proszowice are fertile soil.

We must also remember what is hidden underground, i.e. natural resources. Iron ores, zinc ores, lead ores, copper ores and silver ores. And in the Dąbrowa Basin, huge deposits of hard coal, which in 1880 were estimated for 400 years of exploitation. Although not coking coal, its layers reach 20 m. In the southern counties: Olkusz and Będzin, the deposits contain reserves of zinc ores, lead luster and iron ore. From zinc ores, we will encounter here: calamine (zinc silicate) in varieties called red calamine and white calamine, as well as brown iron ores very rich in zinc.

Old Polish Industrial Region.

The Ivanogródzko – Dąbrowska Iron Road passed through three governorates: Radom, Kielce and Piotrków. The line contributed to the renewal of the Old Polish Basin. The Old Polish Industrial Region (or Old Polish Basin or Old Polish Industrial Basin) is the oldest industrial region in Poland, located in the Świętokrzyskie, Mazowieckie and Łódź provinces. Developed metallurgical industry, means of transport, machinery, construction materials, fine ceramics and iron industry. The Old Polish Industrial Region includes the areas of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, the Kamienna River valley, the Suchedniowski Plateau, the Iłżecki Foothills, and partly the Gielniowski Garb. The main industrial centers are: Kielce, Końskie, Ostrowiec Świętokrzyski, Starachowice and Skarżysko-Kamienna. Some sources also mention Radom as part of the region.

The Dąbrowa Basin.

The Dąbrowa Basin is a historical and industrial region in southern Poland, in the Silesian Voivodeship. It includes cities such as Dąbrowa Górnicza, Sosnowiec, Będzin, Czeladź, and Jaworzno. It is part of the larger metropolitan area of Upper Silesia, but unlike it, it has strong ties to Lesser Poland. The Dąbrowa Basin is not Silesia. The name “Dąbrowa Basin” comes from Dąbrowa Górnicza, one of the main centers of the region, and the mining activity that has been key here since the 19th century.

The greatest development of the Zagłębie took place in the 19th century, when after the third partition of Poland (1795) these lands found themselves within the borders of Prussia, and later, after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, in the Kingdom of Poland under the dictate of the Moscow state.

Thanks to economic reforms and the construction of infrastructure (including the Warsaw-Vienna Railway), the region became one of the most important industrial centers in this part of Europe. Coal mines, iron and zinc smelters, and industrial plants were established. Sosnowiec and Dąbrowa Górnicza transformed from small settlements into dynamically developing cities.

During the Great World War, the region found itself under Germanic and Austro-Hungarian occupation. After Poland regained independence in 1918, the Zagłębie became part of the Second Polish Republic.

During the Second World War, the Dąbrowa Basin was incorporated into the Raj, and its inhabitants were subjected to repression, displacement and death in concentration camps. After the war, in the times of the Polish People’s Republic, there was further industrialization, expansion of cities and development of heavy industry; especially steel and mining.

After the fictitious fall of communism in 1989 (there was no vetting and decommunization), the region had to go through a difficult process of industrial restructuring. Mines and steelworks were closed, which led to economic and social problems. Today, the Dąbrowa Basin is developing as a center of modern economy, focusing on new technologies, education and the service sector.

Currently (2025), the Dąbrowa Basin remains an important region of Poland, being part of the Upper Silesian – Zagłębie Metropolis. Its inhabitants emphasize a distinct cultural and historical identity, often contrasting with the Upper Silesian traditions. Although heavy industry plays a smaller role, the region focuses on the development of new branches of the economy, such as logistics, IT and services. The dynamic development of universities, infrastructure and the proximity of the Silesian agglomeration mean that Zagłębie Dąbrowskie remains an important point on the map of Poland.

Huta Bankowa.

Huta Bankowa is one of the oldest and most important industrial plants in the Dąbrowa Basin, located in Dąbrowa Górnicza. It was established in the 19th century and played a key role in the development of the metallurgical industry in Poland. The steelworks was founded in 1834, on the initiative of the Bank of Poland, hence its name; Huta Bankowa. It was part of a larger plan for the industrialization of the Kingdom of Poland, which was then under the rule of the Moscow state. At that time, the Dąbrowa Basin was becoming an important industrial center, mainly due to the development of mining and metallurgy. The first metallurgical furnaces were launched in the 1830s. The steelworks quickly became one of the most modern metallurgical plants in the Kingdom of Poland, specializing in the production of iron and steel. In the second half of the 19th century, as a result of further industrialization and technological development, Huta Bankowa began to develop dynamically. In 1856, the first coke-fired blast furnace was launched, which significantly increased production efficiency. Thanks to its convenient location, close to coal and ore deposits and on the Warsaw-Vienna Railway line, the steelworks became one of the most important steelworks in the Kingdom of Poland. Among other things, it produced railway rails, which was crucial for the development of railways in the region and the entire Moscow state. The Bankowa Steelworks was one of the largest steelworks centres in Europe. Only the English steelworks equalled it. Although historians emphasise that the Bankowa Steelworks was oversized and not very profitable, let us remember that it is very difficult to maintain the profitability of the steelworks. At that time, steelworks were profitable if they had their own deposits of iron ore and hard coal, and additionally access to cheap and almost unlimited energy. Steelworks operate in a cyclical industry. Growth in construction, communication (bridges, viaducts, locomotives, wagons) or the machine industry increases the demand for steel, which promotes profitability.

During the Great World War, the steelworks suffered as a result of war operations, but after Poland regained independence in 1918, the plant was rebuilt and once again became one of the leading steel producers. During the Second World War, Huta Bankowa was taken over by Germans, who continued its operations for war purposes. After the end of the war, during the Polish People’s Republic, the steelworks was nationalized and became one of the key industrial plants in Poland. Various steel products were produced here, including sheets, bars and structural elements. Currently (2025), Huta Bankowa operates as part of the international concern ArcelorMittal and specializes in the production of steel products, especially railway wheels and steel forgings.

Ivano-Grodzko – Dąbrowska Railway.

There is no doubt that the Moscow state was and is culturally and technologically backward. The Tsar was never interested in the well-being of its citizens. The Russian Tsar was never interested in the railway and treated it as a threat, not an opportunity for development. Therefore, issuing a concession was associated with major restrictions; mandatory wide gauge, construction of two unnecessary tunnels, construction of transshipment stations with the Prussians and Austro-Hungarians, in a place as far away from Moscow as possible, with simultaneous exchange of goods in Kaliningrad, and therefore close to St. Petersburg.

The designer and builder of the Bzin – Dąbrowa section of the line was primarily a resident of Sosnowiec at the time, engineer Stanisław Zieliński. The line was built in the planned time; 3.5 years. 18,000 workers worked on the construction.

On December 21, 1883, the first section from Dęblin, via the bridge over the Vistula to Kielce, was put into operation. On the other hand, the Kielce – Dąbrowa section of the line was launched on January 26, 1885. Initially, the wide gauge ended only in Huta Bankowa, in Dąbrowa Górnicza. In Maczki, a broad-gauge station was built in close proximity to the standard-gauge Granica station. In 1887, the last sections of the line towards Prussia and Austria were completed.

The line was opened on January 26, 1885. A special train, decorated with wreaths and ribbons, ran along the route. The train was carrying delegations of Russian authorities and representatives of railway companies. In one of the train cars sat the chairman of the board of the Ivanogrodzko-Dąbrowska Railway Company, Margrave Zygmunt Wielopolski. On the same day (January 26, 1885), at 4:00 p.m., two scheduled trains set off from Kielce station; one to Dąbrowa, the other to Dęblin. The first train of the Ivanogrodzko-Dąbrowska Railway on the Kielce-Strzemieszyce route was driven by Klemens Możdżeński. He was the former adjutant of General Józef Bem during his national liberation struggles (1846-1848) in Hungary. Initially, the company had about 30 steam locomotives, mainly of Prussian and Moscow production. In St. Petersburg, Prussian locomotives were rebuilt to a wide gauge. Moscow locomotives had Western boilers, and the rest were built in the empire. The company had about 400 freight cars, most of which were manufactured in the Kingdom of Poland. Passenger cars, about 30 of which were also built in factories in the Kingdom of Poland.

Within a few years, the railway line caused the commercial and economic development of cities such as Kielce, Skarżysko Kamienna, Radom, but also smaller cities such as Olkusz and Jędrzejów.

The line brought significant income. That is why the banker Jan Gottlieb Bloch was called the “King of Railways” and in the entire Moscow Empire. The company constantly approached the tsar with proposals to build more lines. But these projects ended up in the trash.

In 1900, the Moscow government’s takeover of all railways in the Kingdom of Poland culminated. The Ivanogródzko-Dąbrowska Railway was incorporated into the Vistula Treasury Railway, whose director was Dmitry Ivanov, director of the former Ivanogródzko-Dąbrowska Railway. Earlier, the Warsaw-Terspolska Railway, the Vistula Railway and others were incorporated into the Vistula Treasury Railway. This was also the time when it was decided to convert the Warsaw-Vienna Railway to a wide gauge (1,524 mm), the only standard gauge line in the Kingdom of Poland, apart from the Warsaw District Railway.

As a result of the Great World War, the Muscovites were pushed far to the east, by the Germans and Austrians. During the fighting, the Muscovites destroyed the railway infrastructure, which did little to slow down the advance of the front to the east. At the same time, the tracks were re-forged to the standard European gauge. After Poland regained independence, all tracks were re-forged to the European gauge.

Written by Karol Placha Hetman